Biometrics have become synonymous with security, but since by definition they are body measurements and calculations related to human characteristics, there are other applications that are driving technology advances in electronics components, including sensors.

The average smartphone user is now comfortable with providing a thumb print to access their mobile device or using facial recognition. Wearables that use biometrics to gather health and fitness information have become somewhat ubiquitous.

In the meantime, a maturing smartwatch means alternative wearables are emerging to meet the demand of industry-specific biometric applications. Research firm IDTechEx foresees a growth in “hearables,” which are headphones or airpods with optical heart-rate sensors. These hearables are poised to play a more advanced role in user-data collection via EEG.

There’s no shortage of examples of how biometric data can be gathered, with smartwatches and fitness tracker bands currently dominating the activity monitoring market by analyzing movements. Raw data from a watch alone has limitations; removable pods that contain the same motion and heart-rate sensors found in smartwatches can be kept in place via pockets in chest straps, underwear, or trousers.

In an interview with Fierce Electronics, IDTechEx technology analyst Tess Skyrme said the value of wearable electronics is that they allow constant and easy access to biometric data through sensors as well as displaying it and actuating a response to it. “The smartwatch is really the flagship,” Skyrme said.

She said continuous biometrics have driven the hype and investment in the wearables market. Wearable biometrics can range from motion and step counts to heart rate and blood oxygen. “But increasingly you're getting more advanced things.” Skin patches allow diabetics to measure their glucose continuously, Skyrme said, while headsets and implants measure things about neural signal and signals from the brain.

“The trend in the wearable space is to increase the number of these biometrics that we can get at through a wearable.” She said it’s an easier way, which saves time and generates value. “It's more comfortable for the user, and that continuous amount of data is also more valuable.”

Sensors for health monitoring are improving

Checking your blood pressure with a click of the button on a wearable is much better than using a traditional blood pressure cuff, but Skyrme said there’s still work that needs to be done on the sensor front. What is commercially available today still needs to be calibrated with a cuff periodically to keep it accurate, she said, which makes it slightly less appealing.

There is innovation, Skyrme said. At this year’s CES, Valencell introduced a blood pressure sensor that clips to the finger and doesn’t require calibration with a cuff. The sensors are the same as those in traditional wearables – PPG sensors – that work with specially-designed algorithms that use the collected data along with personal information and baselines to calculate blood pressure.

Beyond that, other companies are trying to do more with the same optical techniques, Skyrme said, like spectroscopy. “They believe that in the future they'll be able to get a huge range of biometrics out.” A long list of things including glucose, lactose, hydration, and core body temperature are all potentially going to be measured by wearable biometrics.

She said wearables and implants are separate categories, but a lot of the innovation around software and the techniques to analyze the data overlap and interplay, such as electronics that go into the brain to do sensing and convert the neural signal.

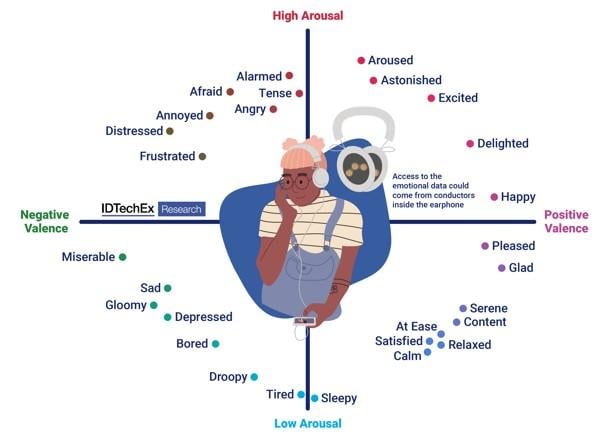

Also, there are efforts to measure neural signals without the need for an implant but with a headband or earbud instead. “That technology is improving, and those sensors are getting more sensitive and more advanced,” Skyrme said. There is a market for something that’s implanted for applications that could help paraplegics to walk, along with the non-invasive wearables that could perhaps one day sense how someone is feeling.

Security applications are how the term ‘biometric’ is thrown around a lot – the difference between biometric and then biometric identification would be where the line is, Skyrme said.

xWearables that use biometrics to monitor health have been a growing market, noted Santiago Del Portillo, global sales engineer at Kensington, including sensors in floor mats and mattress. More advanced biometrics can help detect whether someone is about to have a seizure or monitor ovulation to aid couples who trying to have children, he said, while fitness trackers can now detect dehydration levels and oxygen levels. “All these sensors aid devices to get smarter.”

Regardless of the use case, ultimately a sensor triggers an alert based on rules in software, and subscription-based services are emerging to leverage the biometric data collected by consumer wearables, Del Portillo said. “Biometrics is a hot topic right now.”

Remote work is fueling biometric security

For Kensington, the focus is on security and authentication, which have garnered even more attention with the shift to remote work, he said. From a computing perspective, biometrics for authentication started to gain traction as far back as the launch of Microsoft’s Windows 7 operating system with integrations of biometrics and Windows Hello. “That's what really spiked up the need for an authentication device,” Del Portillo said. The trend gained more momentum in 2018 as Microsoft further pushed biometric authentication.

For security applications, sensors are a key part of the authentication devices built by Kensington, which is integrating technologies by Synaptics. This includes sensors that connect via USB ports on devices, Del Portillo said, as well as embedded biometric sensors on keyboards, mice, and track pads.

These biometric devices are increasingly integrated with other services to support multi-factor authentication (MFA) to make sure the person at the computer is in fact who they claim to be, he said.

While touch is the most familiar type of biometric authentication, voice recognition, iris scanning and face recognition are also becoming more common, all through different peripherals, Del Portillo said. Windows Hello has also spurred the move toward the “password-less” journey, which got an additional bump during the Covid-induced remote work era to enable fast logins and proper authentication.

He said password managers are keeping pace these trends by integrating MFA with biometrics, allowing you to use your fingerprint for what is called “step up” authentication. It aims to strike a balance between security and friction so that users can access some resources with one set of credentials but will need to provide additional credentials to access to more sensitive information.

The next big step forward, however, is behavioral authentication, Del Portillo said. How a user moves their mouse or types, including speed, is used to inform security rules. Geofencing can also complement biometric authentication by setting up a perimeter around a laptop so that if the user steps far enough away, it triggers a rule.

He said biometric detection via webcam with chipsets are ramping up, too, to spot “shoulder surfing” and detect that a person other than an authorized user is looking at the screen. “It can trigger a dimming of the brightness of the screen to make sure that the person cannot see what you are writing.” It could also trigger MFA to allow the user to continue their work. The same webcam can also enable 3D facial recognition by measuring different points of the face using the lens and other sensors. “What we're seeing in the market is more and more sensors that will integrate with biometric authentication devices.”

Connected services drive biometric application opportunities

Del Portillo said the quality of the sensors has improved, which has in turn improved biometrics, while companies such as Synaptics are exploring different materials that can be included in track pads and other devices since the sensor needs to detect a combination of temperature, and the ridge and the placement fingerprint. “The software has gotten better and the materials being used for the sensors also have improved,” he said. “The services running in the background for authentication have improved the accuracy as well as the speed and reliability of fingerprint sensors.”

While MFA and health/fitness are some of the most high-profile applications for biometrics, there’s also opportunities to apply biometrics in the payments space. Swedish biometrics company Fingerprint Cards AB and Italian biometric wearables startup Flywallet recently announced a collaboration to develop and launch biometric wearable products for the European market.

Flywallet’s platform and Keyble wearable are designed to connect payment, health, insurance, mobility, and access services into a single ecosystem. Flywallet is already connected to 25 banks and payment institutions across 32 European nations. The company said it has the first wallet for biometric wearables enabled with tokenization of payment cards like Mastercard and Visa to provide secure digital and contactless payments for integrating its platform. Flywallet is incorporating Fingerprints’ biometric sensors, software, and algorithm into its wearable, which benefits from the technologies’ ultra-low-power consumption.

Fingerprints, meanwhile, has shipped more than one million of its flagship products to customers in the biometric payment card industry. Ultra-thin by design, these fingerprint sensor modules are optimized for integration into payment cards and are also widely used in biometric access cards. The company also sees a lot of potential for cryptocurrency because it can benefit from the security and convenience offered by biometric authentication at the access point and allow users to migrate from relying on PINs and passwords.

Materials, miniaturization are key to innovation

No matter the application, the hardware to support biometric applications is the harder part, although there’s not a lot of room for innovation, IDTechEx’s Skyrme said. Many technologies are mature, such as MEMs, LEDs and optical sensors, even at low power. “The only area where there is some scope for play is in the flexible and printed sensor realm,” she said. “They inherently open up the type of biometrics or metrics that you can get at.”

The rigid sensors that have been perfected will have trouble getting dynamic measurements of stress or strain, Skyrme said. “You're going to struggle to make something truly conformal and really comfortable to the skin.” She said the trend in wearables is moving to something completely flexible – “an electronic skin.”

Further miniaturization advances would potentially allow for helmets to be used instead of an MRI machine, but Skyrme said this is far from the realm of today’s wearable sensors. Noise mitigation is also an area for innovation because it allows for more accuracy and would advance earbud wearables. “By putting your sensor within the ear canal where it's more mechanically stable than on the wrist and other places on the body, you can get much higher fidelity sensing,” she said.

Whoop, which makes a smart band rather a smart watch – there’s no display – has focused on mitigating noise effects by using spatially separated LED sensors to collect more data points, with more than a focus on counting steps and calories burned but also aiding athletes with recovery by collecting more health data like skin temperature and blood oxygen levels.

Skyrme said a big part of moving forward with more non-invasive biometrics will be developing IP around dry electrode materials surface conductance technologies. “Innovation is there in terms of material choice is high,” she said.

RELATED: Stephanie Brown on sensors worn by soldiers for their vital data