Another in a series of previews to Sensors Converge 2023, June 20-22 in Santa Clara, California

Security at the hardware level has become increasingly important – necessary, in fact – with the ubiquity of the internet of things (IoT) and the proliferation of connected vehicles, fully autonomous or otherwise. But is an “unhackable” chip possible?

Defining unhackable is a murky endeavor. Does it mean that the chip itself can not be compromised? Does it mean that the surrounding ecosystem prevents access to the chip? Or does it mean that the time and effort to hack the chip isn’t worth it for the bad guys?

Nir Tasher, Winbond TrustME Secure Flash Technology Executive, told Fierce Electronics in an interview that any security expert knows there’s no such thing as unhackable or unbreakable. He said a more correct statement would be “practically unbreakable within a given timespan” while considering the effort invested in the attempt.

There are also many points of entry that could be attacked, Tasher added. For example, the term “memory” actually refers to a few different types of storage elements, including runtime memory that temporarily holds code and data during the operation of the device. “The information in that memory is lost every power cycle of the system or when the information is replaced with other information during the normal operation of the system,” he said. “Hacking the content of such memory has been the aim of malicious code inserted into the system.”

There are state-of-the-art methods for protecting the content of such memories, Tasher said, but the memories that store data at rest are more appealing to hackers. “This data is not lost when the power is removed from the system,” he said. “These memories are unique in that they can theoretically be removed from the system and accessed directly by hackers, circumventing the system software protection layers.”

Removable chips and memories are more complicated to protect, Tasher said, but their protection is a critical part of making an overall system resilient.

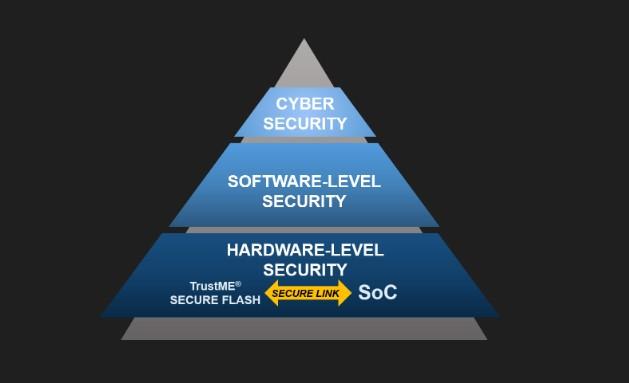

Bill Stewart, VP of Automotive Marketing Americas at Infineon Technologies, said chip security can be tackled in different ways – through the devices themselves, whether it’s the micro controller, the memory, or other components of the system like the networking devices. “You can make those as hard to hack as possible.”

But unhackable is strong term, especially given the unknowns and the challenges involved when it comes to predicting the future and the impact of technologies such as quantum computing. Stewart said Infineon is approaching security at the hardware level by integrating more and more features into its devices so it’s not worth an attacker’s time to compromise it, such as encryption and root of trust.

Automotive, IoT offer many attack surfaces

Infineon is deeply entrenched in the automotive industry, and the modern vehicle is full of chips, ECUs, and microcontrollers – a hacked microcontroller in a steering module could be used to command the car to drive in the wall, Stewart said.

It’s a dramatic example, and the more mundane reality is that chip security needs to ubiquitous as the chips themselves whether used for cars, appliances, solar power systems, industrial robots, or farming equipment.

But security at the hardware level needs software to create an overall secure architecture – it enables upgradeability, Stewart said. This is especially important for vehicles that might be on the road for more than a decade. “We can't put something in a vehicle that's being built today and expect it to be secure for 20 years if we don't have the ability to upgrade it in the field.”

Stewart said over-the-air software updates provide the hardware with the flexibility to accept new algorithms for different types of encryption or different mechanisms of security that also provide some future proofing as well. He said the ability to create layers of security is what ultimately makes a system potentially unhackable.

Software is an essential layer

Sternum is a company focused on adding a layer of security for IoT with a software solution. Amit Serper, director of security research at Sternum, said its two products are designed so that the embedded device they’re installed on cannot be attacked. “Memory attacks are almost completely rendered useless.” He said that in realm of IoT devices, the attack path for a memory corruption or command injection is pretty much always the same. “We are basically eliminating the exploitation route of the attack.”

Serper said you can make something very difficult to attack, but it doesn’t mean that it’s impenetrable or invulnerable; it means there’s a great deal of effort required to compromise the device. “When I hear the word unhackable, I usually get heartburn.”

One of Serper’s current projects is reverse engineering a smart hub that’s deployed around apartment buildings that connects to smart locks – he’s trying to defeat all the security mechanisms on the hub to see if he can create a master key for the entire building. “They put a lot of effort in securing it and encrypting the data on it and using chips that are read only,” he said. “This is an example of something that is supposed to be unhackable.”

It's still a work in progress, but Serper is on the right path. He said it’s just a matter of time, people, and money when it comes to breaking through a device’s security. “Everything is hackable. It's just a question of resources. How much effort do you want to throw against the problem?”

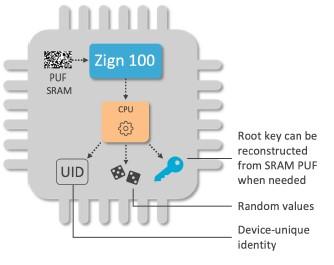

Intrinsic ID’s CEO, Pim Tuyls, also sees unhackable in practical terms, not an absolute. Like Infineon and Sternum, the company is enabling security on devices its recently announced Zign software so that it can be added to a an IoT device already deployed in the field.

In an interview with Fierce Electronics, he said security being baked into the hardware is the inevitable result of putting chips into everything. “It's unfortunately natural.” Each industry has had its own tipping point where chips began to add embedded security, Tuyls said. In the financial services industry, it was the bank card as far back as 20 years ago.

More specialized chips followed with FPGAs add more protection, he added. Defense applications and government were early adopters of hardware-based security in chips, but it was IoT that spurred the need the for more secure chips since 2015, he said, as microcontroller companies realized they need to put additional security into devices.

Implementing security in silicon means physics comes into play, Tuyls said, because it involves physical processes in the chip. At the end of the day, however, a secure chip is built by human beings. “Human beings make mistakes in the implementation and overlook things.”

Tuyls said it’s possible to make a chip that’s that “practically impossible” to hack, just as a data center is not 100% reliable – you can aim for five nines of unhackability, so to speak. “In practice, it's always a balance as a designer that you have to strike between the economics of it and how much security you are going to put on it.”

But for all the talk of connected vehicles and distributed IoT devices being a hacker’s dream with so many attack surfaces to choose from, the data center also benefits from security implemented in hardware.

Security must keep pace with computing power

Chain Reaction is a semiconductor company that’s focused on bringing privacy to the cloud because the cloud is not trusted, said co-founder and CEO Alon Webman in an interview. The reason for doing security at the hardware level is one of efficiency – doing it in software isn’t efficient enough if you’re to keep up with the performance of the CPU.

For data to be safe in the cloud, he said, it needs to be encrypted. “The moment you need to do some kind of processing, there will be a period of time that you have to decrypt the data.” It’s at that moment when there’s a threat of malicious users stealing, looking, or changing the data, even if it's a short, small window, Webman said.

Chain Reaction’s EL3CTRUM hashing ASIC is designed to be efficient and low power and enables customers to create their own hashing system. Webman said there is always a cost for protecting any system – often, it’s increased computation, and a decision has to made whether it’s worthwhile to use the additional computing to protect the data. He said when you build more technologies to protect data and systems, those technologies need to be accelerated in a way that will not have a major effect on the regular operation. “We are helping accelerate technology that protects data.”

Webman said you can have an unhackable chip that’s fully protected but if it can’t really do anything, it doesn’t solve the problem. “It has to be some kind of trade-off,” he said. “You need to be willing to pay something in order to get something, but the payment should be reasonable.”

Intrinsic’s Tuyls likens chip security to keeping a burglar out of a house – they are trying to decide which house they’re going to break into and will ultimately burgle the house with no dogs or cameras, not the house with two dogs and five cameras – it’s about the ROI. “They don't have all the time in the world, so they also pick something where there is a good chance of obtaining a result in the end.”

It’s a question of design, Tuyls said. “How do I put in enough security such that hackers go somewhere else that ROI is small or is even negative? And then, for all practical purposes, it's unhackable.”

Several companies mentioned in this article are presenting or exhibiting at Sensors Converge 2023, running June 20-22 in Santa Clara, California. Registration is online.

Sternum is at booth 706 and Infineon Technologies at booth 762. Sternum Vice President Arthur Braunstein discusses “Who’s Watching the Watchers: Empowering Devices with Reliable and Secure Sensors” at 12:45 p.m. PT on June 21 and Infineon’s Amritraj Khattoi is speaking on “XENSIV Sensors -- at the forefront of sensorization and digitization of things” at 1:20 p.m. PT on June 21. Check out the full list of speakers online.