Working in conjunction with Flemish and European partners, imec will be developing a test environment for driverless cars on motorways over the next three years. The focus in this instance will be on wireless communication and sensor technology for both car and driver. Bart Lannoo, coordinator of the Smart Highway project and the Flemish segment of the CONCORDA project, believes that before we know it, we’ll no longer need a driving license.

Three years to prepare Europe and Belgium for ‘talking’ cars

The European CONCORDA project got underway at the end of 2017. Test sites with communication infrastructure for self-driving cars will be set up or expanded in five countries: Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, France and Belgium. We should point out here that these are not driverless cars along the lines of Google Car. Whereas Google aims to develop cars that will be able to operate completely autonomously from other vehicles, taking their own decisions and driving based on hundreds of sensors, radar units, cameras and a detailed map of the surrounding area, the CONCORDA project instead involves cooperative, connected cars that exchange information with each other and their environment as they carry out a specific ‘task’, ‘together’.

A different sort of test site is being set up in each of the participating countries so that the research can be complementary: freeways with heavy and less heavy traffic, highways with fewer or more exits, supplemented by national, regional and urban roads at specific test sites. In all, twenty-six partners – car manufacturers, telecoms operators and providers, road authorities and research institutions – have joined hands to develop the building blocks needed along the roads and inside the vehicles to create cooperative and connected driverless cars.

The beginning of 2018 saw the start of the first part of the ‘Smart Highway project’, an initiative by the Flemish government. Smart Highway is complementary to the CONCORDA project and focuses on location technology, driver monitoring and the construction of a prototype onboard unit (i.e. the hardware used inside the car so that it can communicate with other vehicles and with the road infrastructure). This onboard unit gives imec the opportunity to use its own software in the car. In fact, what Flanders wants to do is test a whole series of technologies as soon as possible so that vehicles have a smart way of communicating with each other, resulting in fewer traffic jams and accidents. The connected self-driving car is the ultimate goal in this instance.

In the CONCORDA project, imec is working with KU Leuven and the Flemish government’s department for mobility and public works. In the Smart Highway project, we have joined forces with Flanders Make. Imec is coordinating both the Flemish segment of CONCORDA and Smart Highway. This is because imec has a great deal of expertise in connecting driverless cars with each other and having them work together: technology for wireless communication between cars and with the road infrastructure, location technology (using communication networks and radar) and sensors for monitoring the health and alertness of the driver.

Fewer accidents and traffic jams

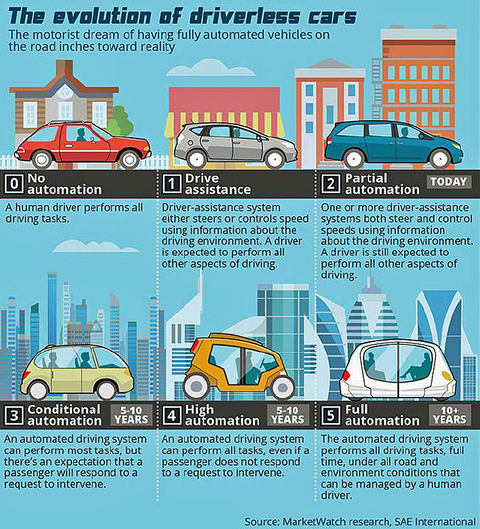

Today, some cars already have highly advanced cruise control systems that don’t allow you to get too close to the car in front of you. They can also tell you when it’s safe to change lanes and they keep an eye on the speed restrictions, etc. Clever: so, what will the next step be?

Experts believe in platoons, in which trucks – and private cars at a later stage – drive along at a short, fixed distance from each other, without the driver having to take any action. In the near term, this will be achievable for trucks that all must take the same route, for example from the port of Antwerp to Rotterdam. In this case, there would be several platoon routes and trucks could join a platoon. The Netherlands – where the CONCORDA project is also running – believes strongly in truck platooning. The system will already be applied commercially in 2019 on a limited scale, for example to drive into and out of the port of Rotterdam.

In Belgium, the focus of the CONCORDA project is on the ‘highway chauffeur’, which is like a highly advanced cruise control for freeways. And to make driving safer, cars will be able to communicate with both the road infrastructure itself, as well as with other vehicles. For instance, they will automatically take note of the road signs (e.g. speed limits), receive plenty of warning in real-time of when there’s roadwork ahead, if there is an obstacle somewhere in the road, when an ambulance is approaching, when there’s a car halted on the roadway or alongside it, etc.

Work is also being carried out on automatic driving systems that operate with other cars (known as ‘cooperative autonomous driving’). What happens is that one car receives information about conditions on the road from other vehicles driving ahead of it and the adaptive cruise control system takes that information into account. ‘Cooperative maneuvering’ is one of the options available. This is where changing lane is a coordinated maneuver that avoids a car having to jam on its brakes suddenly as the result of an unexpected maneuver by another car.

There will also be fewer accidents because cars will be fitted with more and more sensors, radar devices and cameras. The aim is to have cars that ‘know’ and ‘see’ more than the driver. And in the even longer term, exchanging data between cars and the road infrastructure will make it possible for the vehicle to ‘see’ what’s around the corner or what’s happening ten cars ahead. The response time of a ‘machine’ (such as a car) is much faster and it interprets data more reliably than a human.

The Antwerp ring road

The test site in Belgium is in Antwerp: 20 to 30 km of the E313/E34 (Antwerp – Ranst – in the direction of Turnhout). The test site will probably be expanded later to include part of the Antwerp ring road (R01) and the Turnhoutsebaan N12 road that leads to the city center.

Roadside units will be set up containing radios for communicating wirelessly with the project vehicles. Sensors to monitor the weather, road conditions (icy patches, aquaplaning), as well as cameras, etc. may also be installed in these roadside units, in conjunction with the Department for mobility and public works – and depending on the final applications. The first prototypes of the roadside units are likely to be installed during the summer of 2018, while the full installation is planned for the first half of 2019.

There are also project vehicles available, fitted with cameras, radars and lidar units, etc. Ordinary cars can also be used, by adding an onboard unit featuring sensors and radio modules that can read out the data from the car’s CAN Bus unit. Imec will develop a communication platform that acts as an interface to exchange data between the onboard unit, the roadside units and a central cloud platform.

The Technology

To provide communication between cars and the road infrastructure, there are currently two standards/technologies: 4G/LTE-V and Wi-Fi-p. 4G/LTE-V uses the 4G base stations of the telecoms operators (subject to an update for 4G/LTE-V(vehicle)) and hence can operate over greater distances. Wi-Fi-p works over shorter distances and is suitable mainly for direct car-to-car / car-to-roadside communication. Although LTE wasn’t originally developed for this purpose, there is also a short-range LTE-V variant. It is not yet clear which standard the industry and car manufacturers will opt for, or whether they will ultimately incorporate both technologies (like smartphones that have both Wi-Fi and 4G connectivity).

Imec will test the pros and cons of both standards in a range of real-life situations. One very important factor is how stable and reliable communication can be guaranteed always (for example by combining both technologies). Another major parameter is any delay in transmitting the data, which must of course be kept to the minimum (just a few milliseconds, depending on the application).

- To keep the delay as small as possible, distributed computing or mobile edge computing is being researched. Here, the data is processed locally in a cluster of base stations and so does not have to travel to the telecom operator’s cloud first. This concept of mobile edge computing is also of great interest for telecom operators to minimize delay in the future 5G standard.

The danger with driverless cars is that the driver becomes distracted or less alert, such as by falling asleep. This is something that the car also must keep an eye on, which is why imec is working on (radar) sensors fitted in the dashboard that monitor heartbeat and respiration rate, etc. on a constant basis.

The Driverless Car Is coming to collect you from home

Self-driving cars are certainly not something for tomorrow. But trucks driving in platoons – initially at locations such as ports, then on longer routes – is certainly feasible in the short term. After that, there may be taxis that follow fixed routes in cities, or shuttles that drive you around the airport or take you to a student campus – and so on.

And further ahead in the future, perhaps we won’t own a car ourselves, like we do now, but instead be part of a transport service. When that happens, a driverless car will come and pick you up from home at the appointed time and drive you to work, stopping to collect other passengers along the way. All of which means it is entirely feasible that our grandchildren will no longer need a driving license, like we do now.

About the author

Bart Lannoo is a senior business developer at the IDLab-Antwerp research group at the University of Antwerp and imec. Since January 2018 he is also coordinating the Flemish Smart Highway project where imec will deploy a test bed for vehicular communication in Flanders.

Bart received a M.Sc. degree in electro-technical engineering and a Ph.D. degree from Ghent University (Belgium) in July 2002 and May 2008, respectively. Before joining University of Antwerp in April 2016, he has been working at Ghent University and iMinds/imec, where his main research interests were in the field of fixed and wireless access networks, focusing on MAC protocols, Green ICT and techno-economics. He has been involved in several national and European research projects dealing with various topics like optical access, wireless (city) networks, energy-efficient network design and smart manufacturing. He is author or co-author of more than 100 international publications, both in journals and in proceedings of conferences.